Experimental design considerations¶

Last updated: November 28, 2023

Section Overview

🕰 Time Estimation: 30 minutes

💬 Learning Objectives:

- Describe the importance of replicates for RNA-seq differential expression experiments.

- Explain the relationship between the number of biological replicates, sequencing depth and the differentially expressed genes identified.

- Demonstrate how to design an RNA-seq experiment that avoids confounding and batch effects.

Understanding the steps in the experimental process of RNA extraction and preparation of RNA-Seq libraries is helpful for designing an RNA-Seq experiment, but there are special considerations that should be highlighted that can greatly affect the quality of a differential expression analysis.

These important considerations include:

- Proper experiment controls

- Number and type of replicates

- Issues related to confounding

- Addressing batch effects

We will go over each of these considerations in detail, discussing best practice and optimal design.

Controls¶

Experimental controls must be used in order to minimize the effect of variables which are not the interest of the study. Thus, it allows the experiment to minimize the changes in all other variables except the one being tested, and help us ensure that there have been no deviations in the environment of the experiment that could end up influencing the outcome of the experiment, besides the variable they are investigating.

There are different types of controls, but we will mainly see positive and negative controls:

- Negative: The negative control is a variable or group of samples where no response is expected.

- Positive: A positive control is a variable or group of samples that receives a treatment with a known positive result.

It is very important that you give serious thought about proper controls of your experiment so you can control as many sources of variation as possible. This will greatly strengthen the results of your experiment.

Replicates¶

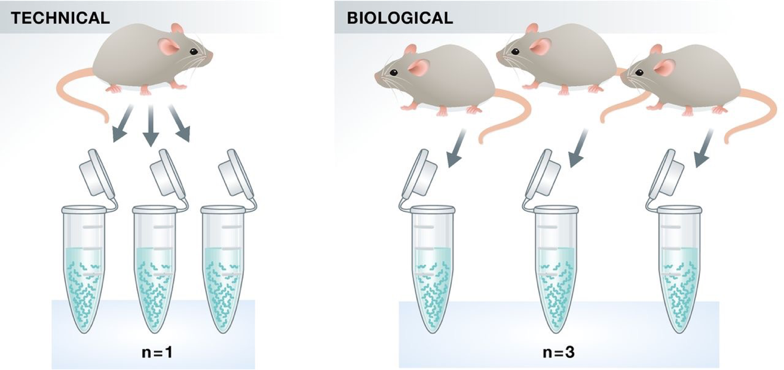

Experimental replicates can be performed as technical replicates or biological replicates.

Image credit: Klaus B., EMBO J (2015) 34: 2727-2730

- Technical replicates: use the same biological sample to repeat the technical or experimental steps in order to accurately measure technical variation and remove it during analysis.

- Biological replicates use different biological samples of the same condition to measure the biological variation between samples.

In the days of microarrays, technical replicates were considered a necessity; however, with the current RNA-Seq technologies, technical variation is much lower than biological variation and technical replicates are unnecessary.

In contrast, biological replicates are absolutely essential for differential expression analysis. For mice or rats, it might be easy to determine what constitutes a different biological sample, but it's a bit more difficult to determine for cell lines. This article gives some great recommendations for cell line replicates.

For differential expression analysis, the more biological replicates, the better the estimates of biological variation and the more precise our estimates of the mean expression levels. This leads to more accurate modeling of our data and identification of more differentially expressed genes.

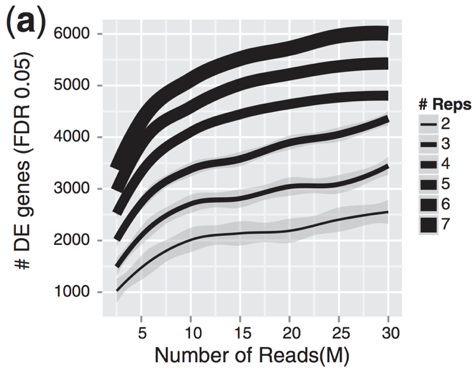

Image credit: Liu, Y., et al., Bioinformatics (2014) 30(3): 301--304

As the figure above illustrates, biological replicates are of greater importance than sequencing depth, which is the total number of reads sequenced per sample. The figure shows the relationship between sequencing depth and number of replicates on the number of differentially expressed genes identified [1]. Note that an increase in the number of replicates tends to return more DE genes than increasing the sequencing depth. Therefore, generally more replicates are better than higher sequencing depth, with the caveat that higher depth is required for detection of lowly expressed DE genes and for performing isoform-level differential expression.

Tip

Sample pooling: Try to avoid pooling of individuals/experiments, if possible; however, if absolutely necessary, then each pooled set of samples would count as a single replicate. To ensure similar amounts of variation between replicates, you would want to pool the same number of individuals for each pooled set of samples.

For example, if you need at least 3 individuals to get enough material for your control replicate and at least 5 individuals to get enough material for your treatment replicate, you would pool 5 individuals for the control and 5 individuals for the treatment conditions. You would also make sure that the individuals that are pooled in both conditions are similar in sex, age, etc.

Replicates are almost always preferred to greater sequencing depth for bulk RNA-Seq. However, guidelines depend on the experiment performed and the desired analysis. Below we list some general guidelines for replicates and sequencing depth to help with experimental planning:

-

General gene-level differential expression:

- ENCODE guidelines suggest 30 million SE reads per sample (stranded).

- 15 million reads per sample is often sufficient, if there are a good number of replicates (>3).

- Spend money on more biological replicates, if possible.

- Generally recommended to have read length >= 50 bp

-

Gene-level differential expression with detection of lowly-expressed genes:

- Similarly benefits from replicates more than sequencing depth.

- Sequence deeper with at least 30-60 million reads depending on level of expression (start with 30 million with a good number of replicates).

- Generally recommended to have read length >= 50 bp

-

Isoform-level differential expression:

- Of known isoforms, suggested to have a depth of at least 30 million reads per sample and paired-end reads.

- Of novel isoforms should have more depth (> 60 million reads per sample).

- Choose biological replicates over paired/deeper sequencing.

- Generally recommended to have read length >= 50 bp, but longer is better as the reads will be more likely to cross exon junctions

- Perform careful QC of RNA quality. Be careful to use high quality preparation methods and restrict analysis to high quality RIN # samples.

-

Other types of RNA analyses (intron retention, small RNA-Seq, etc.):

- Different recommendations depending on the analysis.

- Almost always more biological replicates are better!

What is coverage?

The factor used to estimate the depth of sequencing for genomes is "coverage" - how many times do the number of nucleotides sequenced "cover" the genome. This metric is not exact for genomes (whole genome sequencing), but it is good enough and is used extensively. However, the metric does not work for transcriptomes because even though you may know what % of the genome has transcriptional activity, the expression of the genes is highly variable.

Confounding variables¶

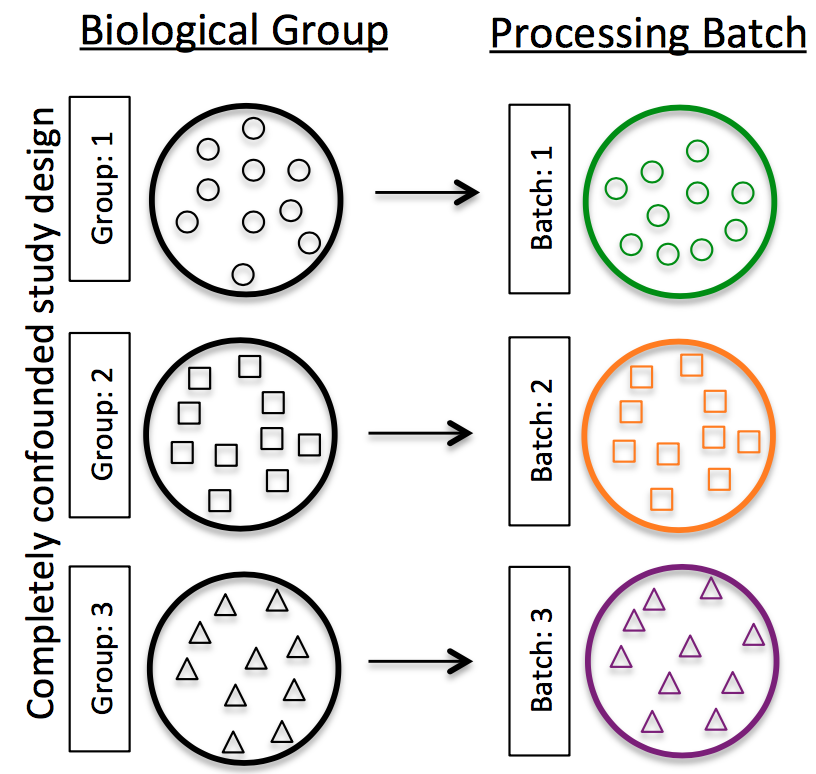

A confounded RNA-Seq experiment is one where you cannot distinguish the separate effects of two different sources of variation in the data.

For example, we know that sex has large effects on gene expression, and if all of our control mice were female and all of the treatment mice were male, then our treatment effect would be confounded by sex. We could not differentiate the effect of treatment from the effect of sex.

To AVOID confounding:

- Ensure animals in each condition are all the same sex, age, litter, and batch, if possible.

- If not possible, then ensure to split the animals equally between conditions

Batch effects¶

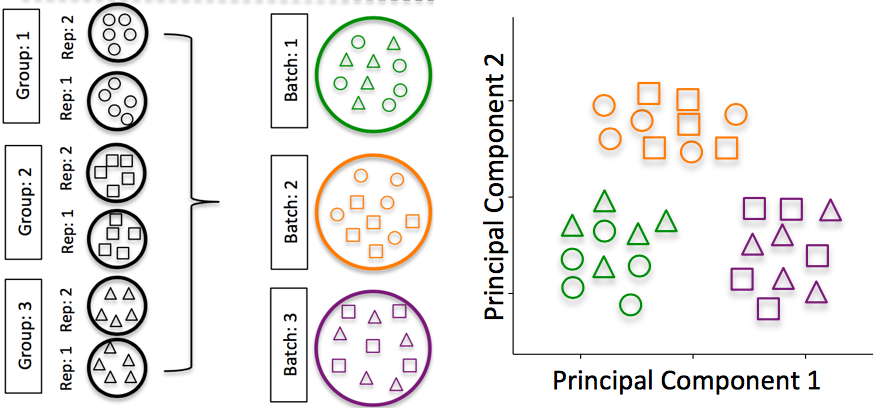

A batch effect appears when variance is introduced into your data as a consequence of technical issues such as sample collection, storage, experimental protocol, etc. Batch effects are problematic for RNA-Seq analyses, since you may see significant differences in expression due solely to the batch effect.

Image credit: Hicks SC, et al., bioRxiv (2015)

To explore the issues generated by poor batch study design, they are highlighted nicely in this paper.

How to know whether you have batches?¶

- Were all RNA isolations performed on the same day?

- Were all library preparations performed on the same day?

- Did the same person perform the RNA isolation/library preparation for all samples?

- Did you use the same reagents for all samples?

- Did you perform the RNA isolation/library preparation in the same location?

If any of the answers is 'No', then you have batches.

Best practices regarding batches¶

- Design the experiment in a way to avoid batches, if possible.

-

If unable to avoid batches:

- Do NOT confound your experiment by batch:

Image credit: Hicks SC, et al., bioRxiv (2015)

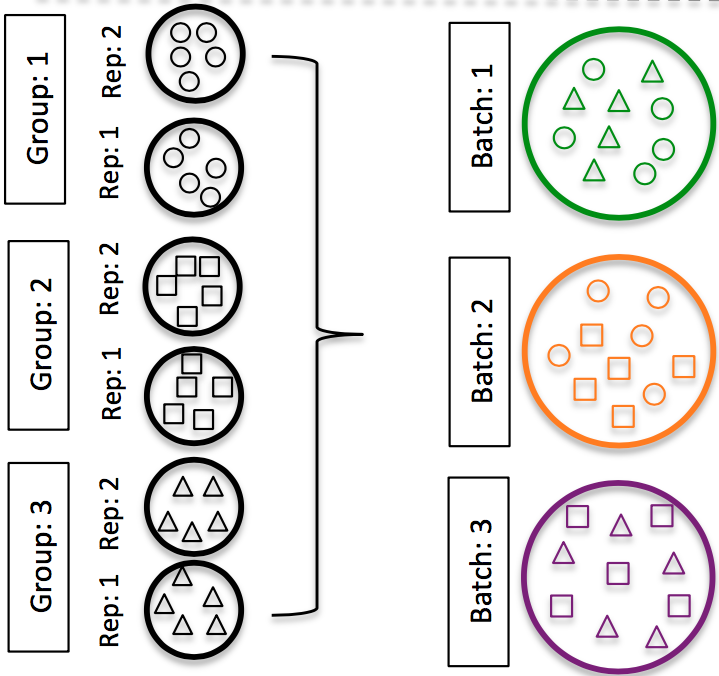

- DO split replicates of the different sample groups across batches. The more replicates the better (definitely more than 2).

Image credit: Hicks SC, et al., bioRxiv (2015)

- DO make a balanced batch design. For example if you can only prepare a subset of samples in the lab on a given day, do not do 90% of samples on day 1 and the remaining 10% on day 2, aim for balance, 50% each day.

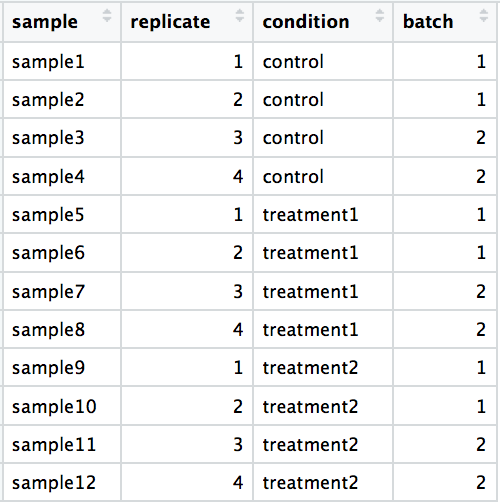

- DO include batch information in your experimental metadata. During the analysis, we can regress out the variation due to batch if not confounded so it doesn't affect our results if we have that information.

Warning on sample preparations

The sample preparation of cell line "biological" replicates "should be performed as independently as possible" (as batches), "meaning that cell culture media should be prepared freshly for each experiment, different frozen cell stocks and growth factor batches, etc. should be used (read more about it here)." However, preparation across all conditions should be performed at the same time.

This lesson was originally developed by members of the teaching team (Mary Piper, Meeta Mistry, Radhika Khetani) at the Harvard Chan Bioinformatics Core (HBC).

Created: November 28, 2023