4. Documentation for biodata

⏰ Time Estimation: X minutes

💬 Learning Objectives:

- The role of documentation in effective management

- Best practices to create metadata and README files

- Sources for controlled vocabularies

- (Optional) Create a database and a catalog browser

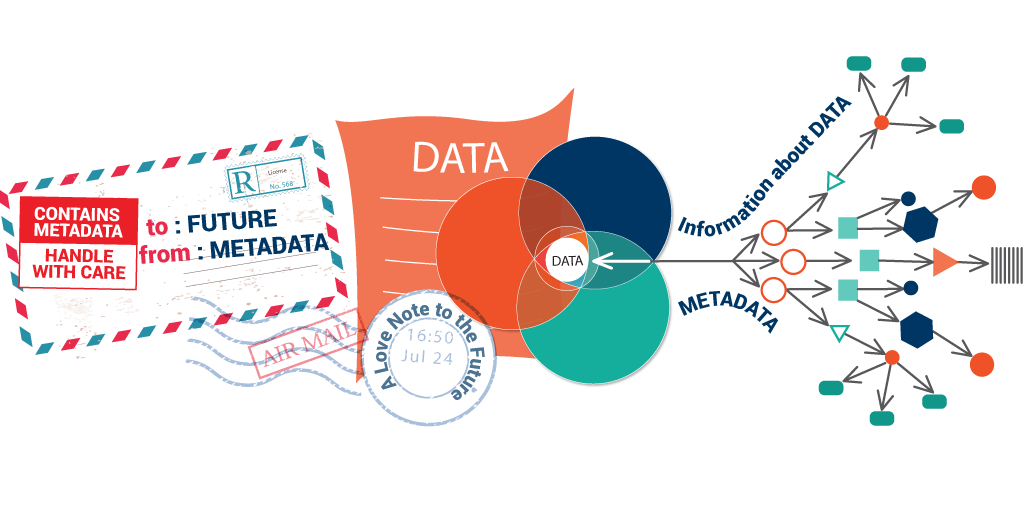

In bioinformatics data management, documentation plays a critical role in ensuring clarity and reproducibility. Documentation and metadata are essential components in ensuring your data adheres to FAIR principles.

Data documentation

Essential documentation comes in different forms and flavors, serving various purposes in research. Examples include protocols outlining experimental procedures, detailed lab journals recording experimental conditions and observations, codebooks explaining concepts, variables, and abbreviations used in the analysis, information about the structure and content of a dataset, software installation, and usage manual, code explanation within files or methodological information outlining data processing steps.

From ontotext.com

From ontotext.com

Data documentation provides essential context and structure to (primary) data, enabling researchers to understand its significance and facilitate efficient data management. Some common elements found in metadata for bioinformatics data include:

- Data collection information: source (e.g., organism, tissue or location), date (YYYY-MM-DD format) and time, collection methods employed or experimental conditions.

- Data processing information: data content, data format, data cleaning and transformation such as filtering and normalizations techniques, and software and tools used.

- Data description: variables and attributes, and data types (e.g., categorical, numerical, or textual).

- Biological context: experimental design, biological purpose and relevance and implications in the broader context.

- Data ownership and access: authorship, licensing of the data and details on accessing and sharing.

- Provenance and tracking: version control information over time and citations, such as links to publications or studies that reference the data.

Data documentation also serves as a crucial guide in navigating the complex landscape of data, akin to a cheat sheet for piecing together the puzzle of information. Much like identifying puzzle pieces, metadata provides essential details about data origin, structure, and context, such as sample collection details, experimental procedures, and equipment used. Metadata enables data exploration, interpretation, and future accessibility, promoting effective management and facilitating data usability and reuse.

- Data Context and Interpretation: Aiding in understanding experimental conditions, sample origins, and processing methods, is crucial for accurate results interpretation.

- Data Discovery and Access: Documentation enables easy locating and accessing of specific datasets by quickly identifying relevant data through sample identifiers, experimental parameters, and timestamps.

- Reproducibility and Collaboration: Documentation facilitates experiment replication and validation by enabling colleagues to reproduce analyses, compare results, and collaborate effectively, enhancing the integrity of scientific findings.

- Quality Control and Validation: Documentation supports data quality assessment by tracking the origin and handling of NGS data, allowing the identification of errors or biases to validate analysis accuracy and reliability.

- Long-Term Data Preservation: Documentation ensures preservation over time, facilitating future understanding and utilization of archived datasets for continued scientific impact as research progresses.

Streamlining Metadata Collection

Data and project directories should both include metadata and a README file. Metadata delivers descriptive information about a dataset or project, offering insights for interpreting, using, and sharing the data effectively. README files offer an overview and purpose of the project or dataset, providing instructions and guidance for setting up, running, and using the data or tools. While metadata concentrates on the data itself, README files provide a broader perspective on the overall project or resource.

- Implement a logical structure with clear and descriptive file names.

- Use of controlled vocabularies and ontologies to ensure consistency and efficient data management and interpretation.

- Use a repository and a versioning system

- Make it Machine-readable, -actionable, and -interpretable.

- Develop standards further within your research environment FAIRsharing standards.

- Include all information for others to comprehend and effectively utilize the data.

README.md

Link to the file format database

- Markdown (

.md): commonly used because is easy to read and write and is compatible across platforms (e.g., GitHub, GitLab). Supports formatting like headings, lists, links, images, and code blocks. - Plain Text (

.txt): Simple and straightforward format without any rich formatting and great for basic instructions. Lack the ability of structure content effectively. - ReStructuredText (

.rst): commonly used for python projects. Supports advanced formatting (takes, links, images and code blocks) .

Others such as HTML, YAML and Notebooks.

The README.md file, written in markdown format, provides a detailed description of the folder’s content. It includes information such as the purpose of the data, collection methods, and relevant details. The content might differ based on the purpose of the data.

Select one of the examples below and reflect on how effectively the README communicates important information about the project. Please note that some of the links lead to README files describing databases, while others pertain to software and tools.

- 1000 Genomes Project. You will find several readme files here.

- Homo Sapiens, fasta GRCh38

- IPD-IMGT/HLA Database

- Docker

- Python pandas

Structure for bioinformatics projects.

- Description and relevance the project

- Objectives and aims

- Datasets and software requirements

- Instruction for data interpretation

- Summary of results

- Contributions

- Additional comments or notes

metadata.yml

- XML (eXtensible Markup Language): uses custom tags to describe data and allows for a hierarchical structure.

- JSON (JavaScript Object Notation): lightweight and human-readable format that is easy to parse and generate.

- CSV (Comma-Separated Values) or TSV (tabulate-separate values): simple and widely supported for representing tabular formats. Easy to manipulate using software or programming languages. It is often use for sample metadata.

- YAML (YAML Ain’t Markup Language): human-readable data serialization format, commonly used as project configuration files.

Others such as RDF or HDF5.

Link to the file format database.

Metadata can be written in many file formats (commonly used: YAML, TXT, JSON, and CSV). We recommend YAML format, which is a text document that contains data formatted using a human-readable data format for data serialization. However, choose the format that best suits the project’s needs. The content will be specific to the type of project.

metadata:

project: "Title"

author: "Name"

date: "YYYYMMDD"

description: "Project short description"

version: "1.0"

analysis:

tool: "software"

version: "1.1.1"Some general metadata fields used across different disciplines:

- Project Title: A concise and informative name for the dataset.

- Author(s): The individual(s) or organization responsible for creating the dataset. Include ORCID for identification.

- Date Created: The date when the dataset was originally generated or compiled, in YYYY-MM-DD format.

- Date Modified: The date when the dataset was last updated or modified (YYYY-MM-DD).

- Object ID: The project or assay ID for tracking and reference purposes.

- Description: A short narrative explaining the content, purpose, and context of the project.

- Keywords: Descriptive terms or phrases capturing the main topics and attributes.

- Ethical and Legal Considerations: Information about ethical approvals, consent, and any legal restrictions.

- Version: The version number or identifier, useful for tracking changes.

- Related Publications: Links or references to scientific publications associated with the folder. Always add the DOI.

- Funding Source: Details about the funding agency or source that supported the research or data generation.

- License: The type of license or terms of use associated with the dataset/project.

- Contact Information: Contact details for individuals who can provide further information about the dataset/project.

There is an exercise in the practical material to streamline the creation of metadata files using Cookiecutter, a template-based scaffolding tool.

Create a metadata file with the following description fields: name, date, description, version, authors, keywords, license. Fill it up at the start of the project, when you generate the file structure.

Controlled vocabularies and ontologies

Researchers encountering inconsistent and non-standardized terms (e.g., gene names, disease names, cell types, protein domains, etc.) across datasets may face challenges in data integration. Thus, requiring additional curation time to enable meaningful comparisons. Standardized vocabularies streamline integration, improving consistency and comparability in analysis. Leveraging widely accepted ontologies in the documentation ensures consistent capture of experiment details in metadata fields, aiding data interpretation.

- Biological ontologies for data scientists - Bionty

- Anatomy - Uberon

- Tissue - Uberon

- Chemical compoundsChemical Entities of Biological Interest

- ExperimentalFactor - Experimental Factor Ontology

- Species - NCBI Taxonomy, Ensembl Species

- Disease - Mondo, Human Disease

- Gene - Ensembl, NCBI Gene, Gene ontology,Microarray Gene Expression Society Ontology (MGED)

- Protein - Uniprot

- CellLine - Cell Line Ontology

- CellType - Cell Ontology

- CellMarker - CellMarker

- Phenotype - Human Phenotype, Phecodes, PATO, Mammalian Phenotype, Zebrafish Phenotype

- Pathway - Gene Ontology, Pathway Ontology

- DevelopmentalStage - Human Developmental Stages, Mouse Developmental Stages

- Drug - Drug Ontology

- Ethnicity - Human Ancestry Ontology

- BFXPipeline - largely based on nf-core

- BioSample - NCBI BioSample attributes

- Articles Indexing Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

An ontology is a structured framework representing concepts, attributes, and relationships within a specific domain, aiding knowledge organization and integration. Employing standardized vocabularies, it facilitates effective communication and reasoning between humans and computers. Ontologies are crucial for knowledge representation, data integration, and semantic interoperability, enhancing understanding and collaboration across complex domains.

Standardization improves data discoverability and interoperability, enabling robust analysis, accelerating knowledge sharing, and facilitating cross-study comparisons. Ontologies act as universal translators, fostering harmonious data interpretation and collaboration across scientific disciplines.

You can find three examples of metadata tailored for different purposes NGS data examples: sample metadata, project metadata, and experimental metadata. We suggest exploring controlled vocabularies and metadata standards within your field and seeking additional specialized sources. You will find a few sources at the end of the page.

Database and data catalogs

Metadata can be used to create data catalogs, particularly beneficial for the efficient organization of experimental or sequencing data generated by researchers. While databases can range from simple tabular formats like Excel to sophisticated DataBase Management Systems (DBMS) like SQLite, the choice depends on factors such as complexity and volume of data. Leveraging a DBMS offers advantages like efficient data storage, enhanced security, and rapid data querying capabilities.

Tables as databases

A browsable table can be created by recursively navigating through a project’s folder hierarchy using a script and generating a TSV file (tab-separated values) named, for example, database_YYYYMMDD.tsv. This table acts as a centralized repository for all project data, simplifying access and organization. Consistency in metadata structure across projects is vital for efficient data management and integration, as it aids in tracking all conducted assays. Adhering to a uniform metadata format enables the seamless inclusion of essential information from YAML files into the browsable table.

Write a script (R or Python) that recursively fetches metadata.yml files in a given path. It is important that each subdirectory contains its corresponding metadata.yml.

Requirements:

- Data folder structure: containing all project folders

- YAML metadata files associated with each project

Click on the hint to reveal the solution and a code example for the exercise, which may serve as inspiration.

You can find a thorough guided exercise in the practical material - Exercise 4.

# Load required packages

packages <- c("yaml", "ggplot2", "lubridate")

# Function to recursively fetch YAML files files, read and convert them to a data frame

df = lapply(file_list, yaml::yaml.load_file)

# Save the data frame as a TSV fileSQLite database

An alternative to the tabular format is SQLite, a lightweight and self-contained relational database management system known for its simplicity and efficiency. SQLite operates without the need for a separate server, making it ideal for scenarios requiring minimal resource usage. It excels in tasks involving structured data storage and retrieval, making it suitable for managing experiment metadata. Similar to the previous example, you can use a script that records all the information from the YAML file in a SQLite database.

- Efficient Querying: SQLite databases optimize querying and data retrieval, enabling fast and efficient extraction of specific information.

- Structured Organization: Databases provide structured and organized data storage, ensuring easy access and maintenance.

- Data Integrity: SQLite databases enforce data integrity through constraints and validations, minimizing errors and inconsistencies.

- Concurrency and Multi-User Support: SQLite supports concurrent read access from multiple users, ensuring accessibility without compromising data integrity.

- Scalability: It can handle growing volumes of data without significant performance degradation.

- Modularity and Portability: Databases are self-contained and modular, simplifying data distribution and portability.

- Security and Access Control: SQLite offers security features like password protection and encryption, with granular control over user access.

- Indexing: Support for indexing accelerates data retrieval based on specific columns, particularly beneficial for large datasets.

- Data Relationships: Databases allow for the establishment of relationships between tables, facilitating storage of interconnected data, such as project, assay, and sample information.

Click on the hint to reveal the necessary libraries and some functions, which may serve as inspiration.

You can find a thorough guided exercise, complete with code example, in the practical material - Exercise 4, option B.

# Load required packages

packages <- c("yaml", "ggplot2", "lubridate", "DBI")

# Function to recursively fetch YAML files files, read and convert them to a data frame

df = lapply(file_list, yaml::yaml.load_file)

# Create an SQLite database from a dataframe and insert data

dbConnect(SQLite(), "filenameXXX.sqlite")

dbWriteTable()Catalog browser

To further optimize the use of your metadata and improve the integration of all your lab metadata, you can design a user-friendly catalog browser for your database using tools like Rshiny or Panel. These frameworks provide interfaces for dynamic search, filtering, and visualization, facilitating efficient exploration of database contents.

Creating such a tool with RShiny is straightforward and does not require extensive development knowledge, whether using a TSV file or a SQLite database. In the practical materials, we demonstrate both scenarios and showcase various functionalities for inspiration. SQLite files are particularly advantageous for data fetching and other operations due to their efficient querying and indexing capabilities.

Here’s an example of an SQLite database catalog created by the Brickman Lab at the Center for Stem Cell Medicine. It’s simple yet effective! Clicking on a data row opens the metadata.yml file, allowing access to detailed metadata for that assay.

Go to the practical material for complete exercise instructions and solutions. The code provided can serve as inspiration for you to adapt as needed.

These are some of the libraries required: install.packages(c("shiny", "DT", "DBI"))

You need to define both a user interface (UI) and a server function. The UI (fluidPage()) outlines the app’s layout using for example, the sidebarLayout() and mainPanel() functions for input controls and output displays.

The server function manages data manipulation and user interactions. Use shinyApp() to launch the app once the UI and server are set up.

Here is a simple example of a server function settup including the main parts (additional components provide advanced functionalities):

server <- function(input, output, session) {

# Define a reactive expression for data based on user inputs

data <- reactive({

req(input$dataInput) # Ensure data input is available

# Load or manipulate data here

})

# Define an output table based on data

output$dataTable <- renderTable({

data() # Render the data as a table

})

# Observe a button click event and perform an action

observeEvent(input$actionButton, {

# Perform an action when the button is clicked

})

# Define cleanup tasks when the app stops

onStop(function() {

# Close connections or save state if necessary

})

}Once you’ve finished the previous exercise, consider implementing these additional ideas to maximize the utility of your catalog browser.

- Add a functionality to only select certain columns

uiOutput("column_select") - Add buttons to order numeric columns ascending or descending using

radioButtons() - Use SQL aggregation functions (e.g., SUM, COUNT, AVG) to perform custom data summaries and calculations.

- Add a tab

tabPanel()to create a project directory interactively (and fill up the metadata fields), tips:dir.create(),data.frame(),write.table() - Modify existing entries

- Visualize results using Cirrocumulus, an interactive visualization tool for large-scale single-cell genomics data.

Explore this example with advanced features such as a two-tab layout, filtering by numeric values and matching strings, and a color-customized dashboard here.

- For R Enthusiasts Explore demosfrom the R Shiny community to kickstart your projects or for inspiration.

- For python Enthusiasts If you want to dive deeper into Shiny apps and their various uses (such as dynamic plots or other interactive widgets), Shiny for Python provides live, interactive code throughout its entire tutorial. Additionally, it offers a great tool called Playground, where you can code and test your own app to explore how different features render.

Wrap up

In this lesson, we’ve covered the importance of attaching metadata to your data for future reusability and comprehension. We briefly introduced various controlled vocabularies and provided several sources for inspiration. Implementing ontologies is optional, as their usage complexity varies.

Optionally, if you’ve gone through the lesson, you’ve learned how to use the metadata YAML files to create a database and a catalog browser using Shiny apps. This makes it easy to manage all assays together.

Sources

- RMDKit: https://rdmkit.elixir-europe.org/data_brokering#collecting-and-processing-the-metadata-and-data

- FAIRsharing.org: provide a searchable database of metadata standards for a wide variety of disciplines

Other sources:

- Johns Hopkins Sheridan libraries, RDM. They provide a list of medical metadata standards resources.

- KU Leuven Guidance: https://www.kuleuven.be/rdm/en/guidance/documentation-metadata

- Transcriptomics metadata standards and fields

- NIH standardizing data collection

- Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics (OHDSI) OMOP Common Data Model

Tools and software

- Rightfield: open source tool facilitates the integration of ontology terms into Excel spreadsheet.

- Owlready2: Python package, enables the loading of ontologies as Python objects. This versatile tool allows users to manipulate and store ontology classes, instances, and properties as needed.

- Shiny Apps: easy interactive web apps for data science